Astor Library

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2014) |

| The Astor Library | |

|---|---|

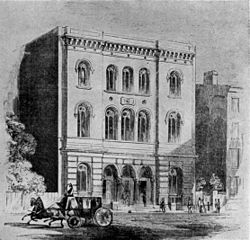

The Astor Library building in 1854 | |

| |

| 40°43′45″N 73°59′30″W / 40.72917°N 73.99167°W | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York, United States |

| Type | Public Research Library |

| Established | January 18, 1849 |

| Dissolved | May 23, 1895 |

| Collection | |

| Size | 294,325 (1895) |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | 225,477 volumes consulted (1895) |

| Type | Library |

| Location | 425 Lafayette St, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°43′45″N 73°59′30″W / 40.729167°N 73.991667°W |

| Area | Manhattan |

| Built | 1850–1853 |

| Restored | January 7, 1987 |

| Architect | Alexander Saeltzer |

| Architectural style(s) | Rundbogenstil |

| Owner | New York City |

| Designated | October 26, 1965 |

| Reference no. | LP-0016 |

The Astor Library was a free public library in the East Village, Manhattan, developed primarily through the collaboration of New York City merchant John Jacob Astor and New England educator and bibliographer Joseph Cogswell and designed by Alexander Saeltzer. It was primarily meant as a research library, and its books did not circulate. It opened to the public in 1854, and in 1895 consolidated with the Lenox Library and the Tilden Foundation to become the New York Public Library (NYPL). During this time, its building was expanded twice, in 1859, and 1881.

Origins

[edit]

In 1836, ill health had obligated Joseph Cogswell to abandon his teaching career and enter the family of Samuel Ward, a New York banker. Three of Ward's sons had been pupils at Round Hill School which Cogswell had administered. Ward introduced Cogswell to John Jacob Astor, who by then was in his 70s and had been retired for about 10 years. As the richest citizen of the United States, German-born Astor was considering what sort of testimonial he should leave to his adopted country.[1]

Early in January 1838, Astor consulted Cogswell about the use of some $300,000–$400,000, which he intended to leave for public purposes. Cogswell urged him to use it for a library, which Astor agreed to.[1] A public announcement of Astor's plan for the establishment of a public library appeared in July 1838. At that point, the sum named was $350,000, and included a lot of land for the necessary building.[2]

One immediate consequence of the announcement was that Astor was beset by innumerable requests for money, and Astor decided to change his planned gift from a donation during his lifetime to a bequest in his will. By March 1839, Cogswell was asking Astor for money to purchase books at an auction, and Astor inquired whether it might not be possible to put the planning for the library into the hands of others, thus freeing himself from all care and trouble about it. Cogswell developed such a strategy, and Astor assented to it on the condition that Cogswell be in charge of buying books.

Cogswell emphasized the necessity for complete planning for the proposed library, not merely for the building and other accommodations, but for the character of the library to be formed, and for the particular topics which Astor wished to have represented most thoroughly. The necessary detail extended to a catalog that must necessarily belong to the collection. This was agreeable to Astor. By May 1839, Astor had set aside a sum of $400,000 for a free public library. For books, $120,000 was allocated, and trustees were to be Washington Irving, William B. Astor, Daniel Lord, Jr., James G. King, Joseph G. Cogswell, Fitz-Greene Halleck, Henry Brevoort, Jr., Samuel B. Ruggles, Samuel Ward III, and the Mayor of New York City and the Chancellor of New York State, ex officio.[3] (The Chancellor later disappeared from the plan when the office was abolished.) In December 1842, $75,000 was fixed as the amount to be expended for the building, and Charles Astor Bristed was added to the list of trustees.

By November 1840, Samuel Ward had died, and Cogswell began residing with Astor and his son William B. Astor. Sometimes he had a downtown office at his disposal. Cogswell was concerned about the progress of the plans for the library, and in 1842, threatened to take an offer to be secretary of legation under Washington Irving, now appointed American minister to Spain. Astor then agreed that more formal work could begin on the library: as soon as the building was finished, Cogswell was to be librarian with a salary of $2,500 a year; meanwhile he was to receive $2,000 while working on the catalog. Thus matters stood until Astor's death in 1848: Cogswell lived with or near Astor, and worked on plans for the library as opportunity offered.

Operation

[edit]Founding

[edit]The first meeting of the trustees came on May 20, 1848. Cogswell was appointed superintendent of the library, with authority to convene the trustees and to preside over their meetings. The name of "The Astor Library" was chosen for the institution at the second meeting on June 1. On September 28, a location was finalized for the building, in what is now the East Village, Manhattan. There it was judged to be tranquil enough to be suitable for study. The lot was valued at $25,000, which sum was deducted from the $400,000 of the endowment.

On January 18, 1849, the library was incorporated,[4] and received a paragraph in the annual message of Governor Hamilton Fish.[5] The trustees appointed by the act were Washington Irving, William Backhouse Astor, Daniel Lord, Jr., James G. King, Joseph Green Cogswell, Fitz-Greene Halleck, Samuel B. Ruggles, Samuel Ward, Jr., Charles Astor Bristed, John Adams Dix, and the Mayor of New York City.[4] In April 1849, the trustees hired a house at 32 Bond Street for temporary custody and exhibition of the books they had purchased. The trustees stated that "all persons desirous of resorting to the library and of examining books, may do so with all the convenience which it is in the power of the trustees to afford." At this time, the total number of books in the library was estimated at over 20,000 volumes, costing $27,009.33.

A German-born architect, Alexander Saeltzer – who had designed Anshe Chesed Synagogue,[6][7][8][9] – was selected as the architect for the building. He designed the building in Rundbogenstil style, then the prevailing style for public building in Germany.[10] The limitation of the cost of the building at $75,000 was stringent: the trustees wanted a building to hold 100,000 volumes at the outset, to afford convenient accommodation for annual additions, to be fireproof, and have the necessary strength; these requirements were by no means easily secured for this sum. W. B. Astor, Cogswell, and Saeltzer drew up specifications and called for bids for construction. All bids exceeded the $75,000 limit: the lowest, by contractors whose ability to finish the work was by no means satisfactorily established, amounted to $81,385.75; the highest, by thoroughly satisfactory contractors, amounted to $107,962. Saeltzer's plan was reworked, and for this plan the construction bid of $75,000, by Peter J. Bogert and James Harriot, was accepted on January 2, 1850.

The cornerstone was laid on March 14, 1850, and the building completed in the summer of 1853. The limit of $75,000 proved an impossible one. William B. Astor bore the expense of $1,590 for groined arches to render the structure more secure from fire, and shelving and apparatus for heating and ventilating were paid for to the amount of $17,141.99 from surplus interest accruing from the funds while the building was in progress and from the premium realized by the advance in market value of United States bonds.

Opening

[edit]

The building was opened to the public on January 9, 1854. Hours were fixed at 10 a.m. to 5 pm. For January no books were available, but visitors were welcome. On February 1, use of books began. The library was closed on Sundays and established holidays. It was a reference library: no books could be taken from the building for any purpose. Admission was free for all persons over 14 years of age. On opening day, the building was stocked with between 80,000 and 90,000 volumes, purchased at a cost of about $100,000. The section on American history was as full as possible. In linguistics, particularly oriental, the library was unsurpassed by any in the United States. The natural sciences were also fully represented, comprising about 7,000 volumes.[11] Cogswell had made his first trip abroad for purchase of books in the winter of 1848–1849, spending something over $20,000. The distracted political state of Europe at the time seemed to offer peculiar advantages for purchases at low rates. Before he sailed, Cogswell reported that during Astor's lifetime he had paid $2,500 for books.

In 1851, Cogswell sailed abroad again. During that summer, he scoured France, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Scandinavia and Germany. The result was an addition of 28,000 volumes secured for $30,000, bringing the total of the collection to about 55,000 or 60,000 volumes, and the total outlay to about $65,000. In November 1852, Cogswell was again authorized to travel to Europe, $25,000 being put at his disposal. He sailed early in December, and remained abroad until March, spending his time mainly in London, Paris, Brussels, Hamburg, and Berlin. The result was the addition of about 25,000 volumes.

The Astor Library's policy of being universally free, to foreigners as well as to United States citizens, also allowed it to successfully apply for donations of important and costly scientific, statistical and historical works published by different governments of Europe. A very practical appreciation of the library was shown by donations received from the federal government, from learned societies and from individuals in various parts of the United States. The state government at Albany sent extensive selections of public documents of New York. In 1855, the British commissioners of patents presented a complete set of their publications, Maine forwarded complete sets of state documents, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island took a similar step in 1856.

In the beginning, there were no printed catalogs of the library to assist readers in choosing books and readers were not admitted within the railing to take down books for examination themselves. There was interest in evening hours, but the increased expense this would have entailed and the danger of fire from gas lighting prevented it. The books were classified using the system in Brunet's Manuel du Libraire which Cogswell thought the most complete and most generally known.

"Everything goes on very smoothly among the habitués of the library, The readers average from one to two hundred daily, and they read excellent books, except the young fry, who employ all the hours they are out of school In reading the trashy, as Scott, Cooper, Dickens, Punch, and the Illustrated News. Even this is better than spinning street yarns, and as long as they continue perfectly orderly and quiet, as they now are, I shall not object to their amusing themselves with poor books."

— Cogswell, to George Ticknor, 24 February 1854, after his library had been open six weeks[12][13][14][15]

For the first year the average daily use was about 100 volumes, with a total for the year of about 30,000. No one topic seemed to dominate the rest, though on the whole the fine arts collection was the most extensively used. The number of readers in the first year varied from 30 for the lowest day to 150 for the highest. For some time, the library was beset by crowds of schoolboys who "come in at certain hours of the day to read, more for amusement than improvement, and shun their classical lessons by the use of English translations." On Cogswell's recommendation, the trustees raised the age limit to 16. In Cogswell's judgment, by this act the library "assumed its proper character, and became a place of quiet study, where every one found ample accommodation."

The question of a catalog was to Cogswell's mind a matter of prime importance. By the end of 1855, Cogswell was able to report that the catalog was finished, excepting only a small portion of history. The collection was grouped into 14 departments, for each of which a separate catalog was prepared. The alphabetical index to these separate catalogs formed the basis of the printed catalog issued during 1857–1861 in 4 volumes. The timing and the format of the catalog went against Cogswell's judgment, but accorded with the desire of the trustees to put before the public a tangible result of their work. In 1866, a supplement was issued. The first catalog recorded approximately 115,000 volumes. The supplement of 1866 recorded the accessions of five years, about 15,000 volumes, and carried with it an index to subjects. It was imperfect, but also the work of someone who knew books and knew how to guide others to them.

Expansion

[edit]

On October 31, 1855, W. B. Astor donated land for the expansion of the Library. Work on an extension began at once. The designer of the addition was Griffith Thomas.[10] The new building was opened to the public on September 1, 1859, the number of volumes in the library being estimated at about 110,000. Washington Irving, president of the board of trustees, died November 28, 1859; he was succeeded as president by W. B. Astor. Cogswell resigned as superintendent in 1861, and Francis Schroeder, former pupil of his at Round Hill and American minister to Sweden in 1850, was appointed in his place. Cogswell still retained his place as a trustee. In 1862 W. B. Astor established an annuity fund of $5,000, yielding $300, payable to Cogswell in return for the bibliographical collection he had presented to the library. In 1864, Cogswell left New York to make his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and resigned as a trustee.

A gift of $50,000 from W. B. Astor came in 1866, of which $20,000 was used for purchase of books, the remainder was for the general funds of the library. This gift brought the sum total presented by him to $300,000, not to mention the installation of a new system of heating apparatus in 1867 for which he paid $6,545.74. Of the $700,000 received from the Astors, father and son (increased about two per cent, by investments, etc.) $283,324.98 was expended for site, building, and equipment; $203,012.38 for books, binding, freight, etc., leaving an endowment fund of $229,000. The income in 1866 was $11,664.31, expenses $8,975.31.

Maturity

[edit]By 1868, those who had been most intimately connected with its founding had nearly all died. The character of the collection was fixed and was known throughout the United States. Schroeder served for 10 years, his resignation being accepted on June 7, 1871. His successor was Edward R. Straznicky, who had been employed in the library since 1859.

The library was a major reference and research resource,[16] but there were detractors. An editorial in The New York Times complained, "Popular it certainly is not, and, so greatly is it lacking in the essentials of a public library, that its stores might almost as well be under lock and key, for any access the masses of the people can get thereto."[17] An article in The Sun of March 4, 1873, reported problems with the mutilation of some of the library's volumes. This was apparently done mostly for convenience: Instead of writing down extracts, readers cut out the sections with the information they needed.[18]

Volumes consulted had increased from 59,516 in 1860 to 135,065 in 1875. In 1875, W. B. Astor died and left $249,000 to the library. Besides this bequest, the library received $10,000 for the purchase of books from his son, John Jacob Astor III, in February 1876. Alexander Hamilton (1816–1889) became president of the board of trustees. In 1876, a beginning was made on a public card catalog. For books purchased since 1866, there was until this time no public index of subjects other than the knowledge possessed by the librarians as to the books on the shelves. At the end of 1877, the library had 177,387 volumes on its shelves.

Straznicky died in 1876, and J. Carson Brevoort, a trustee, was chosen to be superintendent. In February 1878, Brevoort resigned. His successor was Robbins Little, a graduate of Yale. He retained the position as superintendent until 1896, after the 1895 consolidation. That the library was considered something more than a local institution was demonstrated in 1878 when the United States Sanitary Commission, having completed its task, donated its archives to the library for safe keeping. The archives consisted of all its correspondence, reports, account books, hospital directories, printed reports, histories, maps and charts, claims of some 51,000 soldiers and sailors investigated by it, miscellaneous papers, etc. The library promised that they would be preserved and accessible to the public.

Resource expansion

[edit]By 1879 the library had 189,114 volumes on its shelves. Space was lacking. Thus on December 5, 1879, John Jacob Astor III donated three lots of ground adjoining the northern side of the library's lot for an addition. The designer of this second addition was Thomas Stent. Both expansions followed Saelzer's original design so seamlessly that an observer cannot detect that the edifice was built in three stages.[10] On October 10, 1881, this second addition was open to the public, the library being closed the four months preceding to allow the necessary moving and readjustment.

During 1879 the Japanese government presented a representation of their national literature, embracing the standard works of poetry, fiction, geography, history, religion, philology, together with an assortment of ornamental designs; through Viscount Cranbrook, secretary for India in Beaconsfield's cabinet, the library received a large collection of official publications relating to India; New Zealand, New South Wales, Canada, Italy, France, Prussia were moved also to make valuable contributions of documents and statistical material. The Hepworth Dixon collection of English Civil War pamphlets, about five hundred in number, was presented in 1880 by John Jacob Astor III.

By 1882 nearly half the library was unrecorded in a catalog except in the shape of brief entries noted in manuscript in interleaved copies of the Cogswell catalog, and cards begun by Brevoort in 1876. A new author catalog was decided on, to include titles of all works received since the first catalog was published, and for this work Charles Alexander Nelson was hired in 1881. Nelson was a Harvard graduate fitted for this new task by service in the Harvard library and by a wide experience in the Boston book trade. The new printed catalog covered up to 1880. It had a fuller quotation of titles than the first one, a more extensive analysis of the contents of collected or comprehensive works, and greater attention to securing full names of authors. It appeared in four volumes, 1886–1888. As a catalog and as a printed book, it was a thoroughly satisfactory piece of work. The entire cost of printing was borne by John Jacob Astor III and amounted to nearly $40,000. With the publication complete, Nelson left the library in 1888.

The card catalogs presented a problem of greater complexity. The 1876 card catalog begun by Brevoort recorded a part of the accessions received after 1866. There was one set of cards for the use of the public, and another duplicate set for official use. This was at first mainly a subject or rather a broadly grouped classed catalog. The cards were about 5 inches long by 3 inches (76 mm) high. For author entries reliance was made upon the interleaved copies of the Cogswell printed catalog and upon a set of author cards – by no means a complete record – for public use. In 1880 when work began upon the new printed catalog this card catalog was closed; its author cards were destroyed when the new catalog was issued, but revision of the subject group continued as occasion offered until after the 1895 consolidation. After 1880, three card catalogs continued until the 1895 consolidation: (1) an official "Bulletin", on large cards, for works acquired after 1880, mainly an author arrangement; (2) the public "small card" catalog, a dictionary catalog of authors and subjects; (3) the official "small card" catalog, likewise a dictionary arrangement of authors and subjects, but written on thinner cards. The public catalog was severely criticized in the public press for various idiosyncrasies, example articles being "A Library's Buried Treasures" in The New York Times of June 8, 1881, and in September 1881 a critical letter submitted to the Boston Transcript over the signature of "Delta." The second article was reprinted in the Library Journal of September–October 1881.[19]

During the fifteen years following 1880, there was continuous but uneven growth of resources as signified by the number of volumes on the shelves, an increase from 193,308 in 1880 to 227,652 in 1885, to 248,856 in 1890, and to 294,325 at the end of 1895. Purchases reached their low level in 1888 when 876 volumes were bought, and their high level in 1894 when 6,886 volumes were bought, the sums spent for books and binding being $6,245.06 and $24,074 respectively. Appreciation of the library as shown by statistics of readers grew slowly but steadily, the average number for the decade 1880–1889 being 59,000 readers per year, and for the next six years rising to 70,000. About the same result is indicated by the figures of volumes consulted, the number rising from 146,136 in 1880 to 167,584 in 1890 and to 225,477 in 1895. Also during 1880, the hour for opening was moved at 9 am. Closing time stayed at 5 p.m. except during the short days of the winter months when it took place at 4 or 4:30 pm. Alexander Hamilton, president of the board, died in 1889, and Hamilton Fish was chosen to succeed him as president. After two years, in 1891, Thomas M. Markoe was chosen to the office, which he held until the 1895 consolidation.

Later years

[edit]John Jacob Astor III, son of William B. and grandson of John Jacob Astor, died in 1890, having served as trustee since 1858 and as treasurer since 1868. By his will, $400,000 was left to the library. As William Waldorf Astor declined to fill the vacancy, the board ceased to have an Astor on it. At the time of consolidation the trustees, in order of seniority, were Markoe, Henry Drisler, John Lambert Cadwalader, Henry C. Potter, Stephen Van Rensselaer Cruger, Little, Stephen Henry Olin, King, Charles Howland Russell and Philip Schuyler.

The 1895 consolidation marked the end of the Astor Library. It had been an important factor in the intellectual life of New York, and its influence had not been confined to the political or physical boundaries of the city. There were few scholars or investigators in the latter half of the nineteenth century who had not at some time used its collections. It had been conceived in the mind of Joseph Cogswell, a scholar and book lover, and its growth and development followed closely the policies he had planned and prepared. The popular library and the scholar's library seemed to belong to two irreconcilable categories, though a generation later it was found that the two could co-exist peacefully under the same roof.

The Astor Library suffered from its name. There was actually no proprietorship, and no question of family fiefdom. It was a free public library. But the public, though free to criticize, was reluctant to contribute towards its support. That was left to the Astors.

Later building use

[edit]The NYPL abandoned the building in 1911, and the books were moved to the NYPL's newly constructed building by Bryant Park. In 1920, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society purchased it. By 1965 it was in disuse and faced demolition. The Public Theater (then the New York Shakespeare Festival) persuaded the city to purchase it for use as a theater. It was converted for theater use by Giorgio Cavaglieri. The building is a New York City Landmark, designated in 1965.[20]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Lydenberg 1916 pp.556–557

- ^ Lydenberg 1916 p. 558

- ^ Lydenberg 1916 p. 560

- ^ a b "Astor Library records". New York Public Library Archives. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Lydenberg 1916, p. 565

- ^ Sanders, Ronald (text) and Gillon, Edmund V., Jr. (photographs). The Lower East Side: A Guide to Its Jewish Past in 99 New Photographs New York: Dover Publications (1979)

- ^ Israelowitz, Oscar. Synagogues of New York City: History of a Jewish Community New York: Israelowitz Pub., 2000

- ^ Israelowitz, Oscar. Oscar Israelowitz's Guide to Jewish New York City New York: Israelowitz Pub., 2004

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. "Anshe Chesed Synagogue Designation Report" (February 10, 1987)

- ^ a b c Barbaralee Dimonstein, The Landmarks of New York, Harry Abrams, 1998, p. 107.

- ^ Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- ^ "WHEN DICKENS WAS "TRASH": What the Youngsters of New York City Had to Read in the Year 1854". Mariposa Gazette. Vol. LXII, no. 23. Mariposa, California: California Digital Newspaper Collection. November 11, 1916. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (February 10, 2002). "Streetscapes/The Old Astor Library, Now the Joseph Papp Public Theater; Once It Held Many Pages; Now It Has Many Stages". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ Lydenberg 1916, p. 574

- ^ Cogswell, Joseph Green; Ticknor, Anna Eliot (1874). Ticknor, Anna Eliot (ed.). Life of Joseph Green Cogswell as Sketched in His Letters. Cambridge: Privately printed at the Riverside Press. ISBN 9780608430164. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ "History of the New York Public Library". nypl.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "Editorial: Free Public Libraries". The New York Times. January 14, 1872. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ^ Reprinted in Harry Miller Lydenberg (1923). History of the New York Public Library. New York: The New York Public Library. pp. 57–58.

- ^ Dewey, Melvil; Bowker, Richard Rogers; Pylodet, L.; Leypoldt, Frederick; Cutter, Charles Ammi; Weston, Bertine Emma; Brown, Karl; Wessells, Helen E. (September–October 1881). "The Astor Library". Library Journal. 6: 259–261.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1., p.64

Bibliography

[edit]- Lydenberg, Harry Miller (July 1916). "A History of the New York Public Library". Bulletin of the New York Public Library. 20 (6).

Further reading

[edit]- "Astor Library, N. York." Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companon 3:200. Boston, September 25, 1852.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (9th ed.). 1878. This source calls the style of the library building "Byzantine."

- "A Library's Buried Treasures". The New York Times. June 8, 1881.

- "About a Literary Centre: Folks One Sees in the Astor Library Neighborhood". The New York Times. December 11, 1892.

- . . 1914.