Battle of Hamburger Hill

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2016) |

| Battle of Hamburger Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

US Army photographers climb Hill 937 at Dong Ap Bia after the battle, May 1969 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt, Maj. John Collier |

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

29th Regiment

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~1,800 infantry Artillery and air-strike support | 2 battalions, ~800 infantry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

US Claim: 630 killed (body count) 3 captured 89 individual and 22 crew-served weapons recovered[4][5] | ||||||

Location within Vietnam | |||||||

The Battle of Hamburger Hill (13–20 May 1969) was fought by US Army and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces against People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) forces during Operation Apache Snow of the Vietnam War. Though the heavily-fortified Hill 937, a ridge of the mountain Dong Ap Bia in central Vietnam near its western border with Laos, had little strategic value, US command ordered its capture by a frontal assault, only to abandon it soon thereafter. The action caused a controversy among both the US armed services and the public back home, and marked a turning point in the U.S. involvement.[6]

The battle was primarily an infantry engagement, with the US troops moving up the steeply sloped hill against well-entrenched troops. Attacks were repeatedly repelled by the PAVN defenses. Bad weather also hindered operations. Nevertheless, the Airborne troops took the hill through direct assault, causing extensive casualties to the PAVN forces.

Background

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Local Degar tribesmen call the mountain Ap Bia, "the mountain of the crouching beast." Official histories of the engagement refer to it as Hill 937 after the elevation displayed on US Army maps, but the US soldiers who fought there dubbed it "Hamburger Hill," suggesting that those who fought on the hill were "ground up like hamburger meat." "Have you ever been inside a hamburger machine? We just got cut to pieces by extremely accurate machinegun fire," recalled a sergeant.[7]

Terrain

[edit]The battle took place on Dong Ap Bia (Ap Bia Mountain, Vietnamese: Đồi A Bia) in the rugged, jungle-shrouded mountains of South Vietnam, 1.2 miles (1.9 km) from the Laotian border.[8] Rising from the floor of the western A Sầu Valley, Ap Bia Mountain is a solitary massif, unconnected to the ridges of the surrounding Annamite Range. It dominates the northern valley, towering some 937 meters (3,074 ft) above sea level. Snaking down from its highest peak are a series of ridges and fingers, one of the largest extending southeast to a height of 900 meters (2,953 ft), another reaching south to a 916-meter (3,005 ft) peak. The entire mountain is a rugged wilderness blanketed in double- and triple-canopy jungle, dense thickets of bamboo, and waist-high elephant grass.

Order of battle

[edit]The battle on Hamburger Hill occurred in May 1969, during Operation Apache Snow, the second part of a three-phased campaign intended to destroy PAVN Base Areas in the remote A Sầu Valley. This campaign was a series of operations intended to do damage to the PAVN forces in the A Sầu Valley, which had been an infiltration route into South Vietnam prior to 1966, when the PAVN seized the Special Forces camp in the valley during the Battle of A Shau and established a permanent presence. Subsequent US efforts were aimed at damaging enemy forces in the valley rather than attempting to clear or occupy the valley. Lieutenant General Richard G. Stilwell, commander of XXIV Corps, amassed the equivalent of two divisions, and substantial artillery and air support, to once again launch a raid into the valley. The PAVN had moved their 6th, 9th, and 29th Regiments into the area to recover from losses sustained during a previous United States Marine Corps operation (Operation Dewey Canyon) in February.

Assigned to Apache Snow were three airmobile infantry battalions of the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), commanded by Major General Melvin Zais. These units of the division's 3rd Brigade (commanded by Colonel Joseph Conmy) were the 3d Battalion, 187th Infantry (Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt); 2d Battalion, 501st Infantry (Lt. Col. Robert German); and the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry (Lt. Col. John Bowers). Two battalions of the ARVN 1st Infantry Division (the 2/1st and 4/1st) had been temporarily assigned to the 3d Brigade in support. Other major units participating in Apache Snow included the 9th Marine Regiment; and 3d Squadron, 5th Cavalry and the 3rd ARVN Regiment.

Planning

[edit]Colonel Conmy characterized the operation as a reconnaissance in force. His plan called for the five battalions to "combat assault" into the valley by helicopter on 10 May 1969, and to search their assigned sectors for PAVN troops and supplies. The overall plan of attack called for the Marines and the 3/5th Cavalry to reconnaissance in force toward the Laotian border, while the ARVN units cut the highway through the base of the valley. The 501st and the 506th were to destroy the PAVN in their own operating areas and block escape routes into Laos. If a battalion made heavy contact with the PAVN, Conmy would reinforce it by helicopter with one of the other units. In theory, the 101st could reposition its forces quickly enough to keep the PAVN from massing against any one unit, and a US battalion discovering a PAVN unit would fix it in place until a reinforcing battalion could lift in to cut off its retreat and destroy it.

The US and the ARVN units participating in Apache Snow knew, based on existing intelligence information and previous experience in the A Sầu, that the operation was likely to encounter serious resistance from the PAVN. However, they had little other intelligence as to the actual strength and dispositions of PAVN units. The area was extremely remote and difficult to access. Aerial surveillance was difficult, and US battalion commanders had to generate their own tactical intelligence by combat patrols, capturing equipment, installations, documents, and occasionally prisoners of war to provide the raw data from which to draw their assessment of the PAVN order of battle and dispositions. It was this time-consuming and hit-or-miss task force which characterized the main efforts of Colonel Honeycutt's 3/187th Infantry during the first four days of the operation.

Initially, the operation went routinely for the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile). Its units experienced only light contact on the first day, but documents captured by 3/187th indicated that the PAVN 29th Regiment, nicknamed the "Pride of Ho Chi Minh" and a veteran of the 1968 Battle of Hue, was somewhere in the valley. Past experience in many of the larger encounters with PAVN indicated they would resist violently for a short time and then withdraw before the Americans brought overwhelming firepower to bear against them. Prolonged combat, such as at Dak To and Ia Drang, had been relatively rare. Honeycutt anticipated his battalion had sufficient capability to carry out a reconnaissance on Hill 937 without further reinforcement, although he did request that the brigade reserve, his own Company B, be released to his control.

Honeycutt was a protégé of General William C. Westmoreland, the former commander of the US forces in Vietnam. He had been assigned command of the 3/187th in January and had by replacement of many of its officers given it a personality to match his own aggressiveness. His stated intention was to locate the PAVN force in his area of responsibility and to engage it before it could escape into Laos.

Rather than retreat, the PAVN in the valley determined to stand and to fight in a series of well-prepared concentric bunker positions on Hill 937.

Battle

[edit]

Reinforcing the assault on Hill 937

[edit]Having made no significant contacts in its area of operations, at midday on 13 May, the 3rd Brigade commander, Colonel Conmy, decided it would move to cut off PAVN reinforcement from Laos and to assist Honeycutt by attacking Hill 937 from the south. Company B was heli-lifted to Hill 916, but the remainder of the 3/187th made the movement on foot, from an area 4 kilometers (2.5 mi) from Hill 937, and both Conmy and Honeycutt expected the 1/506th to be ready to provide support no later than the morning of 15 May. Although Company B seized Hill 916 on 15 May, it was not until 19 May that the 3/187th as a whole was in position to conduct a final assault, primarily because of nearly impenetrable jungle.

The 3/187th conducted multi-company assaults on 14 May, incurring heavy casualties, while the 1/506th, led by 1st. Lt. Roger Leasure, made probing attacks on the south slopes of the mountain on 16 and 17 May. The difficult terrain and well organized PAVN forces continually disrupted the tempo of the US tactical operations on Hills 916, 900, and 937. Steep gradients and dense vegetation provided few natural landing zones (LZs) in the vicinity of the mountain and made helicopter redeployments impractical. The terrain also masked the positions of the PAVN 29th Regiment, making it nearly impossible to suppress anti-aircraft fire, while the jungle covered the movement of PAVN units so completely that it created a nonlinear battlefield. PAVN soldiers, able to maneuver freely around the LZs, shot down or damaged numerous helicopters with small arms fire, Rocket-propelled grenades, and crew-served weapons. The PAVN also assaulted nearby logistical support LZs and command posts at least four times, forcing deployment of units for security that might otherwise have been employed in assaults. Attacking companies had to provide for 360-degree security as they maneuvered, since the terrain largely prevented them from mutually supporting one another. PAVN platoon- and company-sized elements repeatedly struck maneuvering US forces from the flanks and rear.

Tactical difficulties

[edit]

The effectiveness of US maneuver forces was limited by narrow trails that funneled attacking companies into squad or platoon points of attack, where they encountered PAVN platoons and companies with prepared fields of fire. With most small arms engagements thus conducted at close range, US fire support was also severely restricted. Units frequently pulled back and called in artillery fire, close air support, and aerial rocket artillery, but the PAVN bunkers were well-sited and constructed with overhead cover to withstand bombardment. During the course of the battle the foliage was eventually stripped away and the bunkers exposed, but they were so numerous and well constructed that many could not be destroyed by indirect fire. Napalm, recoilless rifle fire, and dogged squad and platoon-level actions eventually accounted for the reduction of most fortifications, though at a pace and price thoroughly unanticipated by American forces.

US command of small units was essentially decentralized. Though Honeycutt constantly prodded his company commanders to push on, he could do little to coordinate mutual support until the final assaults, when the companies maneuvered in close proximity over the barren mountain top. Fire support for units in contact was also decentralized. Supporting fires, including those controlled by airborne forward air controllers, were often directed at the platoon level. Eventually human error led to five attacks by supporting aircraft on the 3/187th, killing seven and wounding 53. Four of the incidents involved Cobra gunship helicopters, which in one case were more than 1 kilometer (0.62 mi) away from their intended target.

Hamburger Hill

[edit]

On 16 May Associated Press correspondent Jay Sharbutt learned of the ongoing battle on Hill 937, traveled to the area and interviewed MG Zais, in particular asking why infantry, rather than firepower, was used as the primary offensive tool on Hill 937. More reporters followed to cover the battle, and the term "Hamburger Hill" became widely used. The US brigade commander ordered a coordinated two-battalion assault for 18 May, 1/506th attacking from the south and 3/187th attacking from the north, trying to keep the 29th Regiment from concentrating on either battalion. Fighting to within 75 meters (246 ft) of the summit, Company D, 3/187th nearly carried the hill but experienced severe casualties, including all of its officers. The battle was one of close combat, with the two sides exchanging small arms and grenade fire within 20 meters (66 ft) of one another. From a light observation helicopter, the battalion commander attempted to coordinate the movements of the other companies into a final assault, but an exceptionally intense thunderstorm reduced visibility to zero and ended the fighting. Unable to advance, 3/187th again withdrew down the mountain. The three converging companies of 1/506th struggled to take Hill 900, the southern crest of the mountain, encountering heavy opposition for the first time in the battle. Because of the heavy casualties already sustained by his units and under pressure from the unwanted attention of the press, Zais seriously considered discontinuing the attack but decided otherwise. Both the corps commander and the COMUSMACV General Creighton W. Abrams, publicly supported the decision. Zais decided to commit three fresh battalions to the battle and to have one of them relieve the 3/187th in place. The 3/187th's losses had been severe, with approximately 320 killed or wounded, including more than sixty percent of the 450 troops who had assaulted into the valley. Two of its four company commanders and eight of twelve platoon leaders had become casualties. The battalion commander of the 2/506th, Lt. Col. Gene Sherron, arrived at Honeycutt's command post on the afternoon of 18 May to coordinate the relief. 3/187th was flying out its latest casualties, and its commander had not yet been informed of the relief. Before any arrangements were made, Zais landed and was confronted by Honeycutt, who argued that his battalion was still combat effective. After a sharp confrontation, Zais relented, although he assigned one of Sherron's companies to Honeycutt as reinforcement for the assault.

Final assault

[edit]

Two fresh battalions, the 2/501st Infantry and ARVN 2/3d Infantry, were airlifted into landing zones northeast and southeast of the base of the mountain on 19 May. Both battalions immediately moved onto the mountain to positions from which they would attack the following morning. Meanwhile, the 1/506th for the third consecutive day struggled to secure Hill 900.

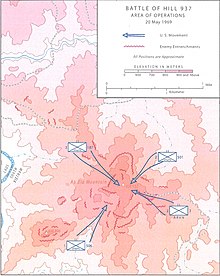

The 3rd Brigade launched its four-battalion attack at 10:00 on 20 May, including two companies of the 3/187th reinforced by Company A 1/506th. The attack was preceded by two hours of close air support and ninety minutes of artillery preparatory fires. The battalions attacked simultaneously, and by 12:00 elements of the 3/187th reached the crest, beginning a reduction of bunkers that continued through most of the afternoon. Some PAVN units were able to withdraw into Laos, and Hill 937 was secured by 17:00.

ARVN participation

[edit]The ARVN 2nd Battalion, 3rd Regiment, 1st Division participated in the battle. Author Andrew Wiest wrote in 2007, particularly based on the statements by General Creighton W. Abrams in "The Abrams Tapes," says its role in the final assault was as follows: The unit was positioned on a stretch of the PAVN defense line that was lightly defended, and sent a scout party to test the forward enemy lines earlier than the proposed assault time; this party was quickly able to discern the minimal enemy strength. The 2/3 commanding officer decided to exploit the situation, and attack in advance of the other units. The 2/3 reached the crest of Hamburger Hill around 10:00, ahead of the 3/187th, but was ordered to withdraw from the summit because allied artillery was to be directed on to the top of the hill. The opportunity to threaten the PAVN lines facing the 3/187th was lost. Shortly after the 2/3 completed their withdrawal, the 3/187th was able to break through the PAVN defenses and occupy the summit.[9]

Aftermath

[edit]Despite the claims that the hill had no real military significance Honeycutt alleged that the hill needed to be taken as it overlooks a good deal of the A Sầu Valley, which was a major supply and staging area for the PAVN.[10]

As it had no real military significance aside from the presence of the PAVN on it, Major General John M. Wright who replaced MG Zais as commander of the 101st Airborne in May abandoned the hill on 5 June as the operations in the valley were concluded. Zais would comment: "This is not a war of hills. That hill had no military value whatsoever." and "We found the enemy on Hill 937 and that's where we fought him."[11]: 22 The battle brought into sharp focus the changing US tactics from Westmoreland's search and destroy operations designed to engage PAVN/VC forces whenever and wherever they were located, to Abrams' new approach of attacking the PAVN/VC logistics "nose," which would be prepositioned to support attacks, and which, if disrupted, would prevent large-scale PAVN/VC attacks.[11]: 22–3

The controversial U.S casualties during the battle lead to the G.I underground newspaper “G.I says” in Vietnam placing a $10,000 bounty on Honeycutt, leading to multiple unsuccessful fragging attempts against him.[12][13]

The debate over Hamburger Hill reached the United States Congress, with particularly severe criticism of military leadership by Senators Edward Kennedy, George McGovern, and Stephen M. Young. In its 27 June issue, Life magazine published the photographs of 242 Americans killed in one week in Vietnam; this is now considered a watershed event of negative public opinion towards the Vietnam War. While only five of the 241 featured photos were of those killed in the battle, many Americans had the perception that all of the photos featured in the magazine were casualties of the battle.[14][15]

The controversy over the conduct of the Battle of Hamburger Hill led to a reappraisal of US strategy in South Vietnam. As a direct result, to minimize casualties, General Abrams discontinued a policy of "maximum pressure" against the PAVN to one of "protective reaction" for troops threatened with combat action, while simultaneously President Richard Nixon announced the first troop withdrawal from South Vietnam.

US losses during the ten-day battle totaled 72 killed and 372 wounded.[1] To take the position, the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) eventually committed five infantry battalions and ten batteries of artillery. In addition, the US Air Force flew 272 missions and expended more than 500 tons of ordnance.

US estimates of the losses incurred by the PAVN 7th and 8th Battalions of the 29th Regiment included 630 dead (bodies discovered on and around the battlefield); including many found in makeshift mortuaries within the tunnel complex. There is no count of the PAVN running off the mountain, the wounded and dead carried into Laos, or the dead buried in collapsed bunkers and tunnels.[5] During the ten-day battle, US forces captured 89 individual weapons and 22 crew‑served weapons.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Smedberg, M(2008) (2008). Vietnamkrigen: 1880-1980. Historiska Media. p. 211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Battle of Dong Ap Bia - Hill 937 10-21 May 1969" (PDF). Headquarters 101st Airborne Division. 24 May 1969. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Người phụ nữ chỉ huy trận đánh trên 'Đồi thịt băm'". Báo điện tử Tiền Phong. 4 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Battle of Dong Ap Bia - Hill 937 10–21 May 1969" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Battles of the Vietnam War".

- ^ "Why the Battle for Hamburger Hill Was So Controversial". HISTORY. 2023-10-03. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ "Troops count cost of Vietnam's Hamburger Hill – archive, 1969". The Guardian. 2017-05-24. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-05-30.

- ^ Sheet 6441-IV, Series L7014, Defense Mapping Agency, 2070.

- ^ Wiest, Andrew (2007). Vietnam's Forgotten Army: Heroism and Betrayal in the ARVN. NYU Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780814794678.

- ^ "B-52s pound enemy bunkers on mountain". Toledo Blade. 19 May 1969. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ^ a b Lipsman, Samuel; Doyle, Edward (1984). Fighting for Time (The Vietnam Experience). Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 9780939526079.

- ^ Kenneth Anderberg. 'G.I. Says' (Video) (Documentary). Jason Rosette of Camerado Media.

- ^ "COLONEL ROBERT HEINL: THE COLLAPSE OF THE ARMED FORCES (1971)". Alpha History.

- ^ Lee, J. Edward; Haynsworth, Toby (2002). Nixon, Ford and the Abandonment of South Vietnam. McFarland. p. 20. ISBN 9780786413027.

- ^ "Faces of the American Dead in Vietnam: One Week's Toll, June 1969". Life Magazine. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Zaffiri, Samuel, Hamburger Hill, May 10- May 20, 1969 (1988), ISBN 0-89141-706-0

- Linderer, A, Gary, Eyes Behind The Lines: L Company Rangers in Vietnam, 1969 (1991) ISBN 0-8041-0819-6

- Boccia, Frank, The Crouching Beast: A United States Army Lieutenant's Account of the Battle for Hamburger Hill, May 1969 (2013), ISBN 978-0786474394