Salt Spring Island

Salt Spring Island | |

|---|---|

Ganges Harbour on Salt Spring island | |

| Nickname(s): Salt Spring, SSI | |

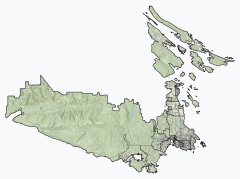

Location of Salt Spring Island within the Capital Regional District | |

| Coordinates: 48°48′24″N 123°29′31″W / 48.806637°N 123.492029°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Regional district | Capital |

| Government | |

| • MP | Elizabeth May (Green) |

| • MLA | Rob Botterell (GRN) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 182.7 km2 (70.5 sq mi) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 11,635 |

| • Density | 63.7/km2 (165/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| Forward sortation area | |

Salt Spring Island or Saltspring Island is one of the Gulf Islands in the Strait of Georgia between mainland British Columbia, Canada, and Vancouver Island.[1]

The island was initially inhabited by various Salishan peoples before being settled by pioneers in 1859, at which time it was renamed Admiral Island. It was the first of the Gulf Islands to be settled and the first agricultural settlement on the islands in the Colony of Vancouver Island, as well as the first island in the region to permit settlers to acquire land through pre-emption. The island was retitled to its current name in 1910.[2] It is named for the salt springs found in the northern part of the island.

Salt Spring Island is the largest, most populous, and the most frequently visited of the Southern Gulf Islands.

History

[edit]Salt Spring Island, or ĆUÁN (čuʔén), was initially inhabited by Salishan peoples of various tribes.[3][4][5] Other Saanich placenames on the island include: ȾESNO¸EṈ¸ (t̕ᶿəsnáʔəŋ̕) for Beaver Point, S¸ĆUÁN (sʔčuʔén) for Cape Keppel, W̱ENÁ¸NEĆ (xʷən̕en̕əč) for Fulford Harbour, SYOW̱T (syaxʷt) for Ganges Harbour, and ṮÁȽEṈ (ƛ̕éɬəŋ) for Isabella Point.[4][5]

The North side of the island was originally settled mostly by African Americans from California, while the South side was settled by Native Hawaiians known as 'Kanaka'.[3] Other settlers included those from Portugal and the British Isles, including English, Irish, and Scots.[6]

Black settlers left California in 1858 after the state passed discriminatory legislation targeting African-Americans. Before the emigration, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs travelled with two other men up to the colony to interview Governor James Douglas about what kind of treatment they could expect there. The Governor was a Guyanese man of multi-ethnic birth, and assured them that people of African descent in Canada would be fairly treated and that the colony had abolished slavery more than 20 years before. Throughout the 1800s, Vesuvius and Ganges were predominantly African-American communities.[7] Racial tensions arose between August 1867 and December 1868, when three Black men were murdered in the community of Vesuvius Bay. The murderers were largely blamed on the local coastal Indigenous community. Many of the murders remained unsolved by authorities, leading to a hostile environment for Black residents whose population subsequently dwindled.[7] Much of the youth moved away to Victoria, Vancouver, and on occasion to the United States.[7]

The island was the first of the Gulf Islands to be settled by non-First Nations people. According to 1988's A Victorian Missionary and Canadian Indian Policy, it was the first agricultural settlement established anywhere in the Colony of Vancouver Island that was not owned by the Hudson's Bay Company or its subsidiary the Pugets Sound Agricultural Company.[8][9]

Salt Spring Island was the first in the Colony of Vancouver Island and British Columbia to allow settlers to acquire land through pre-emption: settlers could occupy and improve the land before purchase, being permitted to buy it at a cost per acre of one dollar after proving they had done so.[10] Before 1871 (when the merged Colony of British Columbia joined Canada), all property acquired on Salt Spring Island was purchased in this way; between 1871 and 1881, it was still by far the primary method of land acquisition, accounting for 96% of purchases.[10] As a result, the history of early settlers on Salt Spring Island is unusually detailed.[11]

The method of land purchase helped to ensure that the land was used for agricultural purposes and that the settlers were mostly families.[12] Ruth Wells Sandwell in Beyond the City Limit indicates that few of the island's early residents were commercial farmers, with most families maintaining subsistence plots and supplementing through other activities, including fishing, logging, and working for the colony's government.[13] Some families later abandoned their land as a result of lack of civic services on the island or other factors, such as the livestock-killing cold of the winter of 1862.[14]

During World War II, 77 Japanese Canadian families living on Salt Spring Island were forcibly relocated away from the coast due to the Internment of Japanese Canadians. Gavin C. Mouat was appointed Custodian of the properties they left behind. Despite evidence of verbal reassurances given to the families in which Mouat said "when you come back, not one chopstick will be missing from your home,"[15] Mouat sold the properties below market value using his Custodial rights without the consent of the owners. Salt Spring Lands Ltd., of which Mouat was the president, ended up purchasing some of the properties. Only one of the interned families, the Murakami's, purchased property on the island again and returned.[16][17]

During the 1960s, the island became a political refuge for United States citizens, this time for draft evaders during the Vietnam War.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The island was known as "Chuan" or "Chouan" Island in 1854, but it was also called "Salt Spring" as early as 1855, because of the island's salt springs.[19]

In 1859, it was officially named "Admiralty Island" in honour of Rear-Admiral Robert Lambert Baynes by surveyor Captain Richards, who named various points of the island in honour of the Rear-Admiral and his flagship, HMS Ganges.[19] Even while named "Admiralty Island", it was referred to popularly as Salt Spring, as in James Richardson's report for the Geological Survey of Canada in 1872.[8][20]

According to records of the Geographic Board of Canada, the island was officially retitled Saltspring on March 1, 1910,[19] though the year 1905 is given by unofficial sources.[8] According to the Integrated Land Management Bureau of British Columbia, locals incline equally to Salt Spring and Saltspring for current use.[19] The official chamber of commerce website for the island, which gives a date of 1906 for the renaming, adopts the two word title, stating that the Geographic Board of Canada, in choosing the one word name, "cared nothing for local opinion or Island tradition."[21]

Geography and locale

[edit]Located between Mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, Salt Spring Island is the most frequently visited of the Gulf Islands as well as the most populous, with a 2016 census population of 10,557 inhabitants.[22] The largest village on the island is Ganges. The island is known for its artists.[18][23] In addition to Canadian dollars, island banks and some island businesses accept Salt Spring's own local currency, the Salt Spring dollar.[21][24]

The island is part of the Southern Gulf Islands, (Salt Spring Island, Galiano Island, Pender Island, Saturna Island, Mayne Island), which are all part of the Capital Regional District, along with the municipalities of Greater Victoria. Salt Spring Island's highest point of elevation is Bruce Peak, which according to topographic data from Natural Resources Canada is just over 700 m (2,300 ft) above sea level.

Climate

[edit]Salt Spring Island has a temperate warm-summer mediterranean climate (Csb) and experiences warm, dry summers and cool winters.[25]

| Climate data for Saltspring Island (St. Mary's Lake) 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1975-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

41.0 (105.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.1 (35.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.0 (14.0) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

−11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 162.1 (6.38) |

98.5 (3.88) |

88.6 (3.49) |

56.8 (2.24) |

43.0 (1.69) |

37.4 (1.47) |

23.2 (0.91) |

28.0 (1.10) |

33.1 (1.30) |

94.0 (3.70) |

167.9 (6.61) |

154.3 (6.07) |

987.0 (38.86) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 152.0 (5.98) |

95.5 (3.76) |

86.2 (3.39) |

56.8 (2.24) |

43.0 (1.69) |

37.4 (1.47) |

23.2 (0.91) |

28.0 (1.10) |

33.1 (1.30) |

93.5 (3.68) |

163.5 (6.44) |

142.8 (5.62) |

955 (37.58) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 10.1 (4.0) |

3.1 (1.2) |

2.4 (0.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (0.2) |

4.4 (1.7) |

11.5 (4.5) |

32 (12.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 19.4 | 15.7 | 17.4 | 14.5 | 11.6 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 7.7 | 15.2 | 20.9 | 20.4 | 164.2 |

| Average rainy days | 18.3 | 15.2 | 17.1 | 14.5 | 11.6 | 9.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 7.7 | 15.1 | 20.2 | 19.2 | 160.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 6.1 |

| Source: Environment Canada[26] | |||||||||||||

Hiking and cycling

[edit]Salt Spring Island has many hiking trails. Two of these trails are rough and windy trails that lead to the summit regions of both Bruce Peak 709 m (2,326 ft) above sea level,[27] and Mount Tuam 602 meters (1,975 feet) above sea level. These two mountain peaks are the tallest points of land on the Southern Gulf Islands. Short hikes can also be found on the island. One of these is the 2 km (1.2 mi) long trek to the summit of Mount Erskine, which is 436 m (1,430 ft) above sea level.[28]

Cycling on Saltspring Island may involve large elevation changes and poor road conditions with limited curb space.[29]

Notable residents

[edit]- Michael Ableman – author, organic farmer

- Don Arney – inventor

- Randy Bachman – musician, songwriter, and CBC personality (moved off island)

- Nick Bantock – author and artist (former resident of Salt Spring Island)

- Robert Bateman – wildlife artist[30]

- Arthur Black – CBC personality and humorist (deceased)

- Brian Brett – poet and novelist (moved away)

- Howard Busgang – comedian and television producer

- Michael Colgan – nutritionist/bodybuilding writer (moved off island)

- Jane Eaton Hamilton ("Hamilton") – novelist, poet, short story writer, essayist (1986–1991; 2017–)

- Bill Henderson – singer-songwriter (The Collectors, Chilliwack)

- Robert Hilles – poet and novelist

- Tom Hooper – singer, songwriter, co-founder of the Grapes of Wrath

- Chris Humphreys – actor, playwright and novelist

- Scott Hylands – actor

- Dan Jason – author, organic farming advocate

- Mary Kitagawa – educator

- Sky Lee – artist and novelist

- Peter Levitt – poet and translator

- Pearl Luke – author

- Derek Lundy – author

- Tara MacLean – musician and singer-songwriter

- Harry Manx – musician and singer-songwriter

- Stuart Margolin – actor and director (The Rockford Files—former resident of Salt Spring Island) (deceased)

- James Monger – PhD award-winning geologist

- Malcolm Muggeridge – English journalist, author, soldier, spy, Christian apologist, (deceased)

- Kathy Page – writer

- Kevin Patterson – medical doctor and writer

- Briony Penn – University of Victoria professor, author, and environmental activist

- Olivia Poole – inventor

- Jan Rabson – voice-over actor

- Raffi – singer-songwriter [30]

- Bruce Reid – local businessman

- Eric Roberts – British intelligence officer

- Clare Rustad – Canada women's national soccer team and family doctor

- Harley Rustad – journalist and author

- Hannah Simone – actor, producer, writer (New Girl)

- Malcolm Smith – motorcyclist

- Sylvia Stark – African-American pioneer

- Patrick Taylor – Northern Irish author

- Meg Tilly – actress and novelist

- Valdy – folk and country musician

- Phyllis Webb – poet and radio broadcaster (deceased)

- Simon Whitfield – Olympic triathlon champion

- Ronald Wright – author

Education

[edit]

- Gulf Islands Secondary School

- Salt Spring Island Middle School

- Fulford Elementary School

- Salt Spring Elementary School

- Salt Spring Centre School

- Phoenix School

- Fernwood Elementary School

Transportation

[edit]

Local bus transit on the island is provided by BC Transit.

BC Ferries operates three routes to Salt Spring: between Tsawwassen (on the BC mainland) and Long Harbour (on the east side of Salt Spring), between Swartz Bay (at the north end of Vancouver Island's Saanich Peninsula) and Fulford Harbour (at the south end of Salt Spring), and between Crofton (on the east side of Vancouver Island) and Vesuvius (on the west side of Salt Spring).

Salt Spring Air, Seair Seaplanes and Harbour Air Seaplanes operate floatplane services from Ganges Water Aerodrome to Vancouver Harbour Water Airport and Vancouver International Water Airport. Kenmore Air operates between Ganges and Lake Union, Seattle, United States.

Library

[edit]Library facilities have existed on Salt Spring in one form or another since the early 1930s, but officially formed the Salt Spring Island Public Library Association in 1960. The demand for books and resources has only grown since then, requiring constant expansions over the years to accommodate the needs of the island residents. In December 2012, the new Salt Spring Island Public Library was opened. The library is staffed by two librarians, among other paid positions and 87 volunteers.[31]

Communications

[edit]Telecommunications service providers include Telus and Shaw, with most wireless carriers providing coverage. The Island is served by the Ganges and Fulford Harbour exchanges. Active Radio Amateurs maintain wireless repeaters located on Mt Bruce. 2 meter band (147.320 MHz). Coverage from Nanaimo, Vancouver and Victoria.

Fire Rescue

[edit]Salt Spring Island Fire Rescue (SSIFR) is the primary emergency response agency serving Salt Spring Island,. Established in approximately 1946 to ensure the safety and well-being of the island's residents and visitors, SSIFR provides fire suppression, medical response, technical rescue, and public education services. Responding to approximately 750 calls per year,[32] SSIFR plays a vital role in protecting the unique environment and vibrant community of Salt Spring Island.

Search and Rescue

[edit]The Royal Canadian Marine Search and Rescue Station 25 (RCMSAR25) is volunteer organization operated by the Gulf Island Marine Rescue Society (GIMRS) that maintains a permanent 24/7 marine search and rescue capability in the vicinity of Salt Spring Island BC Canada.[33] The organization responds to marine search and rescue emergencies as well as engaging with the local community through a variety of Marine Safety Awareness and Education Programs.

RCMSAR25 consists of 30+ volunteer members – men and women of all ages - with a search and rescue vessel based at Vesuvius Harbour.

For land based Search and Rescue, Salt Spring Island Search & Rescue has been active in the community since 1989.[34] They are a dedicated group of approximately 40 unpaid professional volunteers trained to search for, rescue and assist missing persons. Members are highly skilled in teamwork, ground search tactics, first aid, wilderness navigation, tracking, survival, radio communications, high-angle rope rescue, and helicopter safety.

See also

[edit]- Long Harbour, British Columbia

- Ruckle Provincial Park

- Wallace Island Marine Provincial Park

- Salt Spring dollar

References

[edit]- ^ "Natural Resources Canada-Canadian Geographical Names (Saltspring Island)". Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ "The Province of British Columbia GeoBC (Saltspring Island)". Retrieved 2014-09-07.

- ^ a b Schulte-Peevers, Andrea (2005). Schulte-Peevers, Andrea (ed.). Canada. Lonely planet (9 ed.). London: Lonely Planet. p. 729. ISBN 978-1-74059-773-9.

Originally settled by the Salish First Nation over a thousand years ago, it became a place where African Americans fled to escape racial tensions in the USA

- ^ a b "Saanich Place Names". Saanich Classified Word List. Retrieved 2012-07-16.

- ^ a b Elliott, Dave. "Saltwater People" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- ^ Sandwell, Contesting, 4.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Brittany (22 February 2009). "Saltspring Island, British Columbia •". Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Hill and Hill, 241.

- ^ Nock, David A.; Canadian Corporation for Studies in Religion (1988). A Victorian Missionary and Canadian Indian Policy: Cultural Synthesis vs. Cultural Replacement. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 0-88920-153-6.

- ^ a b Sandwell, Ruth Wells (1999). Beyond the City Limits: Rural History in British Columbia. UBC Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-7748-0694-X.

- ^ Sandwell, Ruth Wells (2005). Contesting Rural Space: Land Policy and Practices of Resettlement on Salt Spring Island, 1859-1891. McGill-Queen's Press -MQUP. p. 3. ISBN 9780773572638. JSTOR j.ctt80png.

- ^ Sandwell, 89-90.

- ^ Sandwell, Beyond, 90-91.

- ^ Sandwell, Beyond, 93.

- ^ "Keiko Mary Kitagawa, interviewed by Rebeca Salas, 17 June 2017".

- ^ "Dispossession: How B.C. stole the lives of 22,000 Japanese Canadians". Victoria Times Colonist. December 2019. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ Smallshaw, Brian (2017). The dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island (Thesis thesis).

- ^ a b Hill, Kathleen Thompson; Gerald N. Hill (2005). Victoria and Vancouver Island: A Personal Tour of an Almost Perfect Eden (5 ed.). Globe Pequot. p. 242. ISBN 9780762738755.

- ^ a b c d "Origin Notes and History". Integrated Land Management Bureau of British Columbia. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Richardson, James (1872-05-01). "Report on the coal fields of the East Coast of Vancouver Island". Report of Progress - Geological Survey of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada.

Southward of Salt Spring Island, or, as it is named upon the chart, Admiralty Island, are situated

- ^ a b "Visitors: About Salt Spring Island". Salt Spring Island Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 2009-02-16. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ Statcan: 2016 Census

- ^ Thompson, Wayne C.; Jacqueline Grekin (2003). Canada (5 ed.). Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 633. ISBN 2-89464-476-0.

- ^ "Salt Spring Dollars – Community Currency for a Resilient Island".

- ^ Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (2018-10-30). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5 (1). Nature, Sci Data 5, 180214 (2018).: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- ^ Environment Canada — Canadian Climate Normals 1981-2010, accessed 11 September 2017

- ^ "Saltspring Island". British Columbia Travel and Adventure Vacations. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Mount Erskine - Assault Route - Hiking on Salt Spring Island from SaltSpringMarket.com". SaltSpringMarket.com. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ McAdam, Leigh (2013-04-05). "Biking Salt Spring Island in British Columbia". Hike Bike Travel. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Grant (16 May 2016). "Seductive Salt Spring Island". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "History of the Library | Salt Spring Island Public Library". saltspring.bc.libraries.coop. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- ^ "YTD Emergency Calls – Salt Spring Island Fire Rescue".

- ^ "RCMSAR25 Salt Spring Island". RCMSAR25 Salt Spring Island. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Home". Salt Spring Island Search and Rescue. Retrieved 30 August 2024.