History of Turkey

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

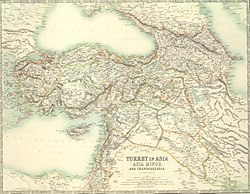

The history of Turkey, understood as the history of the area now forming the territory of the Republic of Turkey, includes the history of both Anatolia (the Asian part of Turkey) and Eastern Thrace (the European part of Turkey). These two previously politically distinct regions came under control of the Roman Empire in the second century BC, eventually becoming the core of the Roman Byzantine Empire. For times predating the Ottoman period, a distinction should also be made between the history of the Turkic peoples, and the history of the territories now forming the Republic of Turkey[1][2] From the time when parts of what is now Turkey were conquered by the Seljuq dynasty, the history of Turkey spans the medieval history of the Seljuk Empire, the medieval to modern history of the Ottoman Empire, and the history of the Republic of Turkey since the 1920s.[1][2]

Prehistory and ancient history

Present-day Turkey has been inhabited by modern humans since the late Paleolithic period and contains some of the world's oldest Neolithic sites.[3][4] Göbekli Tepe is close to 12,000 years old.[3] Parts of Anatolia include the Fertile Crescent, an origin of agriculture.[5] Other important Anatolian Neolithic sites include Çatalhöyük and Alaca Höyük.[6] Neolithic Anatolian farmers differed genetically from farmers in Iran and Jordan Valley.[7] These early Anatolian farmers also migrated into Europe, starting around 9,000 years ago.[8][9][10] Troy's earliest layers go back to around 4500 BC.[6] The Urfa Man statue is dated c. 9000 BC, to the period of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, and is defined as "the oldest known naturalistic life-sized sculpture of a human".[11]

Anatolia's historical records start with clay tablets from approximately around 2000 BC that were found in modern-day Kültepe.[12] These tablets belonged to an Assyrian trade colony.[12] The languages in Anatolia at that time included Hattian, Hurrian, Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic.[13] Hattian was a language indigenous to Anatolia, with no known modern-day connections.[13][14] Hurrian language was used in northern Syria.[13] Hittite, Luwian, and Palaic languages were in the Anatolian sub-group of Indo-European languages,[15] with Hittite being the "oldest attested Indo-European language".[16] The origin of Indo-European languages is unknown.[17] They may be native to Anatolia[18] or non-native.[19]

Hattian rulers were gradually replaced by Hittite rulers.[12] The Hittite kingdom was a large kingdom in Central Anatolia, with its capital of Hattusa.[12] It co-existed in Anatolia with Palaians and Luwians, approximately between 1700 and 1200 BC.[12] As the Hittite kingdom was disintegrating, further waves of Indo-European peoples migrated from southeastern Europe, which was followed by warfare.[20] The Thracians were also present in modern-day Turkish Thrace.[21] It is not known if the Trojan war is based on historical events.[22] Troy's Late Bronze Age layers matches most with Iliad's story.[23]

Around 750 BC, Phrygia had been established, with its two centers in Gordium and modern-day Kayseri.[24] Phrygians spoke an Indo-European language, but it was closer to Greek, rather than Anatolian languages.[15] Phrygians shared Anatolia with Neo-Hittites and Urartu. Luwian-speakers were probably the majority in various Anatolian Neo-Hittite states.[25] Urartians spoke a non-Indo-European language and their capital was around Lake Van.[26][24] Urartu was often in conflict with Assyria,[27] but fell with the attacks of Medes and Scythians in seventh century BC.[24] When Cimmerians attacked, Phrygia fell around 650 BC.[28] They were replaced by Carians, Lycians and Lydians.[28] These three cultures "can be considered a reassertion of the ancient, indigenous culture of the Hattian cities of Anatolia".[28]

Anatolia and Thrace in classical antiquity

Classical Anatolia

The classical history of Anatolia can be roughly subdivided into the classical period and Hellenistic Anatolia, ending with the conquest of the region by the Roman empire in the second century BC.

After the fall of the Hittites, the new states of Phrygia and Lydia stood strong on the western coast as Greek civilization began to flourish. They, and all the rest of Anatolia were relatively soon after incorporated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

As Persia grew in strength, their system of local government in Anatolia allowed many port cities to grow and to become wealthy. All of Anatolia got divided into various satrapies, ruled by satraps (governors) appointed by the central Persian rulers. The first state that was called Armenia by neighbouring peoples was the state of the Armenian Orontid dynasty, which included parts of eastern Turkey beginning in the 6th century BC, which became the Satrapy of Armenia under Achaemenid rule. Some of the satraps revolted periodically but did not pose a serious threat. In the 5th century BC, Darius I built the Royal Road, which linked the principal city of Susa with the west Anatolian city of Sardis.[29]

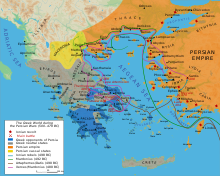

Anatolia played a pivotal role in Achaemenid history. In the earliest 5th century BC, some of the Ionian cities under Persian rule revolted, which culminated into the Ionian Revolt. This revolt, after being easily suppressed by the Persian authority, laid the direct uplead for the Greco-Persian Wars, which turned out to be one of the most crucial wars in European history.

Achaemenid Persian rule in Anatolia ended with the conquests of Alexander the Great, defeating Darius III between 334 and 330 BC. Alexander wrested control of the whole region from Persia in successive battles. After Alexander's death, his conquests were split amongst several of his trusted generals, but were under constant threat of invasion from both the Gauls and other powerful rulers in Pergamon, Pontus, and Egypt. The Seleucid Empire, the largest of Alexander's territories, and which included Anatolia, became involved in a disastrous war with Rome culminating in the battles of Thermopylae and Magnesia. The resulting Treaty of Apamea in (188 BC) saw the Seleucids retreat from Anatolia. The Kingdom of Pergamum and the Republic of Rhodes, Rome's allies in the war, were granted the former Seleucid lands in Anatolia.

Roman control of Anatolia was strengthened by a 'hands off' approach by Rome, allowing local control to govern effectively and providing military protection. In the early 4th century, Constantine the Great established a new administrative centre at Constantinople, and by the end of the 4th century the Roman empire split into two parts, the Eastern part (Romania) with Constantinople as its capital, referred to by historians as the Byzantine Empire from the original name, Byzantium.[30]

Thrace

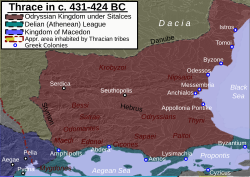

The Thracians (Ancient Greek: Θρᾷκες, Latin: Thraci) were a group of Indo-European tribes inhabiting a large area in Central and Southeastern Europe.[31] They were bordered by the Scythians to the north, the Celts and the Illyrians to the west, the Ancient Greeks to the south and the Black Sea to the east. They spoke the Thracian language – a scarcely attested branch of the Indo-European language family. The study of Thracians and Thracian culture is known as Thracology.

Starting around 1200 BC, the western coast of Anatolia was heavily settled by Aeolian and Ionian Greeks. Numerous important cities were founded by these colonists, such as Miletus, Ephesus, Smyrna and Byzantium, the latter founded by Greek colonists from Megara in 657 BC. All of Thrace, and the native Thracian peoples were conquered by Darius the Great in the late 6th century BC, and were re-subjugated into the empire in 492 BC following Mardonius' campaign during the First Persian invasion of Greece.[32] The territory of Thrace later became unified by the Odrysian kingdom, founded by Teres I,[33] probably after the Persian defeat in Greece.[34]

By the 5th century BC, the Thracian presence was pervasive enough to have made Herodotus[35] call them the second-most numerous people in the part of the world known by him (after the Indians), and potentially the most powerful, if not for their lack of unity. The Thracians in classical times were broken up into a large number of groups and tribes, though a number of powerful Thracian states were organized, such as the Odrysian kingdom of Thrace and the Dacian kingdom of Burebista. A type of soldier of this period called the Peltast probably originated in Thrace.

Before the expansion of the Kingdom of Macedon, Thrace was divided into three camps (East, Central, and West) after the withdrawal of the Persians following their eventual defeat in mainland Greece. Cersobleptes, a notable ruler of the East Thracians, attempted to expand his authority over many of the Thracian tribes but was eventually defeated by the Macedonians.

The Thracians were typically not city-builders. The largest Thracian cities were in fact large villages[36][37] and the only polis was Seuthopolis.[38][39]

Byzantine Period

The Persian Achaemenid Empire fell to Alexander the Great in 334 BC,[40] which led to increasing cultural homogeneity and Hellenization in the area.[41] Following Alexander's death in 323 BC, Anatolia was subsequently divided into a number of small Hellenistic kingdoms, all of which became part of the Roman Republic by the mid-1st century BC.[42] The process of Hellenization that began with Alexander's conquest accelerated under Roman rule, and by the early centuries AD the local Anatolian languages and cultures had become extinct, being largely replaced by ancient Greek language and culture.[43][44]

In 324, Constantine I chose Byzantium to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, renaming it New Rome. Following the death of Theodosius I in 395 and the permanent division of the Roman Empire between his two sons, the city, which would popularly come to be known as Constantinople became the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. This, which would later be branded by historians as the Byzantine Empire, ruled most of the territory of what is today Turkey until the Late Middle Ages,[45] while the other remaining territory remained in Sassanid Persian hands.

Between the 3rd and 7th century AD, the Byzantines and the neighboring Sassanids frequently clashed over possession of Anatolia, which significantly exhausted both empires, thus laying the way open for the eventual Muslim conquests from both empires' respective south.

The borders of the empire fluctuated through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the empire reached its greatest extent after the fall of the west, re-conquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including Africa, Italy and Rome, which it held for two more centuries. The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 exhausted the empire's resources, and during the early Muslim conquests of the 7th century, it lost its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, to the Rashidun Caliphate. It then lost Africa to the Umayyads in 698, before the empire was rescued by the Isaurian dynasty.

The fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 marked the end of the Byzantine Empire. Refugees fleeing the city after its capture would settle in Italy and other parts of Europe, helping to ignite the Renaissance. The Empire of Trebizond was conquered eight years later when its eponymous capital surrendered to Ottoman forces after it was besieged in 1461. The last Byzantine rump state, the Principality of Theodoro, was conquered by the Ottomans in 1475.

Early history of the Turks

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

Historians generally agree that the first Turkic people lived in a region extending from Central Asia to Siberia. Historically they were established after the 6th century BC.[46] The earliest separate Turkic peoples appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BC[46] (contemporaneous with the Chinese Han Dynasty).[47] The first mention of Turks was in a Chinese text that mentioned trade of Turk tribes with the Sogdians along the Silk Road.[48]

It has often been suggested that the Xiongnu, mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic speakers.[49][50][51][52][53]

The Hun hordes of Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century AD, may have been Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.[47][54][55] Some scholars argue that the Huns were one of the earlier Turkic tribes, while others argue that they were of Mongolic origin.[56]

In the 6th century, 400 years after the collapse of northern Xiongnu power in Inner Asia, leadership of the Turkic peoples was taken over by the Göktürks. Formerly in the Xiongnu nomadic confederation, the Göktürks inherited their traditions and administrative experience. From 552 to 745, Göktürk leadership united the nomadic Turkic tribes into the Göktürk Empire. The name derives from gok, "blue" or "celestial". Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khanate had its temporary khans from the Ashina clan that were subordinate to a sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khanate retained elements of its original shamanistic religion, Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khanate was also the first state known as "Turk". Towards the end of the century, the Göktürks Khanate was split in two; i.e., Eastern Turkic Khaganate and Western Turkic Khaganate. The Tang Empire conquered the Eastern Turkic Khaganate in 630 and the Western Turkic Khaganate in 657 in a series of military campaigns. However, in 681 the khanate was revived. The Göktürks eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but the name "Turk" was later taken by many states and peoples. [citation needed]

Turkic peoples and related groups migrated west from Turkestan and what is now Mongolia towards Eastern Europe, Iranian plateau and Anatolia and modern Turkey in many waves. The date of the initial expansion remains unknown. After many battles, they established their own state and later created the Ottoman Empire. The main migration occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East.[57] They also participated in the Crusades.

Seljuk Empire

The Seljuq Turkmens created a medieval empire that controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. From their homelands near the Aral Sea, the Seljuqs advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia. [58]

The Seljuq/Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016–1063) in 1037. Tughril was raised by his grandfather, Seljuk-Beg Seljuk gave his name to both the Seljuk empire and the Seljuk dynasty. The Seljuqs united the fractured political scene of the eastern Islamic world and played a key role in the first and second crusades. Highly Persianized in culture and language, the Seljuqs also played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition, even exporting Persian culture to Anatolia.[59] A dynasty from Seljuks, the Seljuks of Rum, became the ruling power in Anatolia. After Mongol invasion of Anatolia, Seljuks of Rum collapsed.[60]

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman beylik's first capital was located in Bursa in 1326. Edirne which was conquered in 1361[61] was the next capital city. After largely expanding to Europe and Anatolia in 1453, the Ottomans nearly completed the conquest of the Byzantine Empire by capturing its capital, Constantinople during the reign of Mehmed II. Constantinople was made the capital city of the Empire following Edirne. The Ottoman Empire would continue to expand into the Eastern Anatolia, Central Europe, the Caucasus, North and East Africa, the islands in the Mediterranean, Greater Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Arabian peninsula in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries.

The Ottoman Empire's power and prestige peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent. The empire was often at odds with the Holy Roman Empire in its steady advance towards Central Europe through the Balkans and the southern part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[62] In addition, the Ottomans were often at war with Persia over territorial disputes, which allowed them to inherit the Timurid Renaissance. At sea, the empire contended with the Holy Leagues, composed of Habsburg Spain, the Republic of Venice and the Knights of St. John, for control of the Mediterranean. In the Indian Ocean, the Ottoman navy frequently confronted Portuguese fleets in order to defend its traditional monopoly over the maritime trade routes between East Asia and Western Europe; these routes faced new competition with the Portuguese discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488. The Ottomans even had influence in Southeast Asia as the Ottomans sent soldiers to their most distant vassal, the Sultanate of Aceh[63] at Sumatra in Indonesia. Their forces in Aceh were opposed by the Portuguese that had crossed the Atlantic and Indian Oceans invaded the Sultanate of Malacca and the Spaniards who had crossed from Latin America and invaded formerly Muslim Manila in the Philippines, as these Iberian powers waged a world war against the Ottoman Caliphate known as the Ottoman–Habsburg wars.

The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 marked the beginning of Ottoman territorial retreat; some territories were lost by the treaty: Austria received all of Hungary and Transylvania except the Banat; Venice obtained most of Dalmatia along with the Morea (the Peloponnesus peninsula in southern Greece); Poland recovered Podolia.[64] Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Ottoman Empire continued losing its territories, including Greece, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya and the Balkans in the 1912–1913 Balkan Wars. Anatolia remained multi-ethnic until the early 20th century. Its inhabitants were of varied ethnicities, including Turks, Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds, Greeks, French, and Italians (particularly from Genoa and Venice). Following the loss of its outer territories and the expulsion of Muslims from former Ottoman Europe, Ottomanist pluralist ideas fell out of favor, replaced by anti-Christian sentiment. [65] Following a coup led by the Committee of Union and Progress, the Ottoman state pursued policies of Turkification,[66] including arbitrary violence against Greeks and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.[67]

Faced with territorial losses on all sides the Ottoman Empire under the rule of the Three Pashas forged an alliance with Germany who supported it with troops and equipment. The Ottoman Empire entered World War I (1914–1918) on the side of the Central Powers and was ultimately defeated.[68] The Ottomans successfully defended the Dardanelles strait during the Gallipoli campaign and achieved initial victories against British forces in the first two years of the Mesopotamian campaign, such as the Siege of Kut; but the Arab Revolt turned the tide against the Ottomans in the Middle East. In the Caucasus campaign, however, the Russian forces had the upper hand from the beginning, especially after the Battle of Sarikamish. In the wake of this defeat, which War Minister Enver Pasha blamed on Armenians siding with Russia, and with Ottoman military units already carrying out massacres against Armenian villages,[69] the CUP adopted a policy of eliminating Armenians[65] in what is now broadly recognized by scholars as the Armenian genocide.[70]

Russian forces advanced into northeastern Anatolia and controlled the major cities there until retreating from World War I with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk following the Russian Revolution. Following World War I, the huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states.[71]

On October 30, 1918, the Armistice of Mudros was signed, followed by the imposition of Treaty of Sèvres on August 10, 1920, by Allied Powers, which was never ratified. The Treaty of Sèvres would break up the Ottoman Empire and force large concessions on territories of the Empire in favour of Greece, Italy, Britain and France.

Republic of Turkey

The occupation of some parts of the country by the Allies in the aftermath of World War I prompted the establishment of the Turkish National Movement.[62] The Turkish Provisional Government in Ankara, which had declared itself the legitimate government of the country on 23 April 1920, started to formalize the legal transition from the old Ottoman into the new Republican political system. The Ankara Government engaged in armed and diplomatic struggle. In 1921–1923, the Armenian, Greek, French, and British armies had been expelled:[72][73][74][75] The military advance and diplomatic success of the Ankara Government resulted in the signing of the Armistice of Mudanya on 11 October 1922. The handling of the Chanak Crisis (September–October 1922) between the United Kingdom and the Ankara Government caused the collapse of David Lloyd George's Ministry on 19 October 1922[76] and political autonomy of Canada from the UK.[77] On 1 November 1922, the Turkish Parliament in Ankara formally abolished the sultanate, thus ending 623 years of monarchical Ottoman rule.

The Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, which superseded the Treaty of Sèvres,[78][79] led to the international recognition of the sovereignty of the new Turkish state as the successor state of the Ottoman Empire. On 4 October 1923, the Allied occupation of Turkey ended with the withdrawal of the last Allied troops from Istanbul. The Turkish Republic was officially proclaimed on 29 October 1923 in Ankara, the country's new capital.[80] The Lausanne Convention stipulated a population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[81]

Mustafa Kemal became the republic's first president and introduced many reforms. The reforms aimed to transform the old religion-based and multi-communal Ottoman monarchy into a Turkish nation state that would be governed as a parliamentary republic under a secular constitution.[82] The fez was banned, full rights for women politically were established, and new alphabet for Turkish based upon the Latin script was created.[83] Among the other things, economic privileges for foreigners were abolished and their means of production and railways were nationalised. Foreign schools were placed under state control. The abolition of the caliphate followed on 3 March 1924. In the same year, Turkey abolished sharia and in 1925, a clothing reform for men (the Hat Law) was enacted.

In the following years, entire legal systems were adopted from European countries and adapted to Turkish conditions. In 1926, Swiss civil law—and thus monogamy with the equality of men and women—was adopted first (gender equality was only partially achieved in everyday life, however), so polygamy was banned. This was followed by German commercial law and Italian criminal law. The Islamic sectarian lodges in 1925 and the Masonic lodges[84][85][86] in 1935 were banned. The high taxes imposed on farmers were reduced. In 1926, the Arabic calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar and the metric system was introduced. In 1927, co-education were introduced. The law on industrial incentives was passed (1927) and the first five-year plan for industry came into force (1934). Secularisation was proclaimed in 1928. An educational mobilisation was initiated to literate the rural population.

With the Surname Law of 1934, the Turkish Parliament bestowed upon Kemal the honorific surname "Atatürk" (Father Turk).[79] Atatürk's reforms caused discontent in some Kurdish and Zaza tribes leading to the Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925[87] and the Dersim rebellion in 1937.[88]

Turkey was neutral in World War II (1939–45) but signed a treaty with Britain in October 1939 that said Britain would defend Turkey if Germany attacked it. An invasion was threatened in 1941 but did not happen and Ankara refused German requests to allow troops to cross its borders into Syria or the USSR. Germany had been its largest trading partner before the war, and Turkey continued to do business with both sides. It purchased arms from both sides. The Allies tried to stop German purchases of chrome (used in making better steel). Starting in 1942 the Allies provided military aid. The Turkish leaders conferred with Roosevelt and Churchill at the Cairo Conference in November, 1943, and promised to enter the war. By August 1944, with Germany nearing defeat, Turkey broke off relations. In February 1945, it declared war on Germany and Japan, a symbolic move that allowed Turkey to join the nascent United Nations.[89][90]

Meanwhile, relations with Moscow worsened, setting stage for the start of the Cold War. The demands by the Soviet Union for military bases in the Turkish Straits, prompted the United States to declare the Truman Doctrine in 1947. The doctrine enunciated American intentions to guarantee the security of Turkey and Greece, and resulted in large-scale U.S. military and economic support.[91]

After participating with the United Nations forces in the Korean War, Turkey joined NATO in 1952, becoming a bulwark against Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean. Following a decade of intercommunal violence on the island of Cyprus and the Greek military coup of July 1974, overthrowing President Makarios and installing Nikos Sampson as a dictator, Turkey invaded the Republic of Cyprus in 1974. Nine years later the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) was established. Turkey is the only country that recognises the TRNC[92]

The one-party period was followed by multi-party democracy after 1945. The Turkish democracy was interrupted by military coups d'état in 1960, 1971 and 1980.[93] In 1984, the PKK began an insurgency against the Turkish government; the conflict, which has claimed over 40,000 lives, continues today.[94] Since the liberalization of the Turkish economy during the 1980s, the country has enjoyed stronger economic growth and greater political stability.[95]

In March 1995, twenty-three people were killed and hundreds were injured in the incidents called Gazi Massacre in Istanbul. The events began with an armed attack on several coffee shops in the neighborhood, where an Alevi religious leader was killed. Protests occurred both in Gazi and Ümraniye district on the Asian side of İstanbul. Police responded with gunfire.[96]

In August 2014, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won Turkey's first direct presidential election.[97]

In July 2016, the Turkish attempted coup took place. A number of rogue government units took over and were only repelled after a few hours.[98]

In December 2016, an off duty policeman Mevlut Altintas shot dead the Russian Ambassador inside an Art Gallery. He refused to surrender and was then shot dead by special police.[99]

In April 2017, the constitutional amendments, which significantly increased the powers of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, were narrowly accepted in the constitutional referendum.[100]

In June 2018, President Erdoğan was re-elected for a new five-year term in the first round of the presidential election. His Justice and Development Party (AK Party) secured a majority in the separate parliamentary election.[101]

In October 2018, Prince MBS of Saudi Arabia sent a group of government agents to murder prominent critic, Jamal Khashoggi, in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul. His death was just a few days before his sixtieth birthday.[102]

In July 2022, the Turkish government asked the international community to recognise Turkey by its Turkish name Türkiye, in part because of the homonym, turkey (bird), for the name of the country in the English language.[103]

In May 2023, President Erdoğan won a new re-election and his AK Party with its allies held parliamentary majority in the general election.[104]

As of May 2023, approximately 96,000 Ukrainian refugees of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine have sought refuge in Turkey.[105] In 2022, nearly 100 000 Russian citizens migrated to Turkey, becoming the first in the list of foreigners who moved to Turkey, meaning an increase of more than 218% from 2021.[106]

As of August 2023, the number of refugees of the Syrian civil war in Turkey was estimated to be 3 307 882 people. The number of Syrians had decreased by 205 894 people since the beginning of the year.[107]

In March 2024, the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) gained a significicant victory in local election, including mayoral victories in Turkey’s five largest cities: Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Bursa, and Antalya.[108]

See also

- Outline of the Ottoman Empire

- History of Anatolia

- History of the Ottoman Empire

- History of Greece

- History of the Kurds

References

- ^ a b "About this Collection – Country Studies". loc.gov. Archived from the original on 12 August 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ a b Douglas Arthur Howard (2001). The History of Turkey. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30708-9. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ a b Howard 2016, p. 24

- ^ Casson, Lionel (1977). "The Thracians" (PDF). The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 35 (1): 2–6. doi:10.2307/3258667. JSTOR 3258667. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ^ Bellwood 2022, p. 224

- ^ a b Howard 2016, p. 25

- ^ Bellwood 2022, p. 229

- ^ Bellwood 2022, p. 229

- ^ Kılınç, Gülşah Merve; Omrak, Ayça; Özer, Füsun; Günther, Torsten; Büyükkarakaya, Ali Metin; Bıçakçı, Erhan; Baird, Douglas; Dönertaş, Handan Melike; Ghalichi, Ayshin; Yaka, Reyhan; Koptekin, Dilek; Açan, Sinan Can; Parvizi, Poorya; Krzewińska, Maja; Daskalaki, Evangelia A. (June 2016). "The Demographic Development of the First Farmers in Anatolia". Current Biology. 26 (19): 2659–2666. Bibcode:2016CBio...26.2659K. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.057. PMC 5069350. PMID 27498567.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Mallick, Swapan; Pósa, Annamária; Stégmár, Balázs; Keerl, Victoria; Rohland, Nadin; Stewardson, Kristin; Ferry, Matthew; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Harney, Eadaoin; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Llamas, Bastien (November 2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. 551 (7680): 368–372. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..368L. doi:10.1038/nature24476. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5973800. PMID 29144465.

- ^ Chacon, Richard J.; Mendoza, Rubén G. (2017). Feast, Famine or Fighting?: Multiple Pathways to Social Complexity. Springer. p. 120. ISBN 9783319484020.

- ^ a b c d e Howard 2016, p. 26

- ^ a b c Steadman 2012, p. 234

- ^ Michel 2012, p. 327

- ^ a b Beckman 2012, p. 522

- ^ McMahon & Steadman 2012a, p. 8

- ^ Heggarty, Paul (2021). "Cognacy Databases and Phylogenetic Research on Indo-European". Annual Review of Linguistics. 7: 371–394. doi:10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011619-030507.

- ^ Bellwood 2022, p. 242

- ^ Melchert 2012, p. 713

- ^ Howard 2016, pp. 26–27

- ^ Ahmed 2006, p. 1576

- ^ Jablonka 2012, pp. 724–726

- ^ McMahon 2012, p. 17

- ^ a b c Howard 2016, p. 27

- ^ Yakubovich 2012, p. 538

- ^ Zimansky 2012, p. 552

- ^ Radner 2012, pp. 738–739

- ^ a b c Howard 2016, p. 28

- ^ A modern study is D.F. Graf, The Persian Royal Road System, 1994.

- ^ ushistory.org. "The Fall of the Roman Empire [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Christopher Webber, Angus McBride (2001). The Thracians, 700 BC–AD 46. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-329-3.

- ^ Joseph Roisman, Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 144435163X pp 135-138, p 343

- ^ D. M. Lewis; John Boardman (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-521-23348-4. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Xenophon (8 September 2005). The Expedition of Cyrus. ISBN 9780191605048. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, Book V Archived 2013-10-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 612. "Thrace possessed only fortified areas and cities such as Cabassus would have been no more than large villages. In general the population lived in villages and hamlets."

- ^ John Boardman, I.E.S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N.G.L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC. Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 612. "According to Strabo (vii.6.1cf.st.Byz.446.15) the Thracian -bria word meant polis but it is an inaccurate translation."

- ^ Mogens Herman Hansen. An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis: An Investigation Conducted by The Copenhagen Polis Centre for the Danish National Research Foundation. Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 888. "It was meant to be a polis but this was no reason to think that it was anything other than a native settlement."

- ^ Christopher Webber and Angus McBride. The Thracians 700 BC-AD 46 (Men-at-Arms). Osprey Publishing, 2001, p. 1. "They lived almost entirely in villages; the city of Seuthopolis seems to be the only significant town in Thrace not built by the Greeks (although the Thracians did build fortified refuges)."

- ^ Hooker, Richard (6 June 1999). "Ancient Greece: The Persian Wars". Washington State University, Washington, United States. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- ^ Sharon R. Steadman; Gregory McMahon (15 September 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (October 2000). "Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C. – 1 A.D. in Timeline of Art History.". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2006.

- ^ David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers; Astrid Biles Beck (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Theo van den Hout (27 October 2011). The Elements of Hittite. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-50178-1. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Daniel C. Waugh (2004). "Constantinople/Istanbul". University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ^ a b Peter Zieme: The Old Turkish Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Empire of the Mongols. Special tape for Exhibition 2005/2006, p. 64

- ^ a b Findley (2005), p. 29.

- ^ "Etienne de la Vaissiere", Encyclopædia Iranica article:Sogdian Trade Archived 2009-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, 1 December 2004.

- ^ Silk-Road:Xiongnu Archived 2015-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Yeni Turkiye Research and Publishing Center". www.yeniturkiye.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Kessler, P L. "An Introduction to the Turkic Tribes". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Early Turkish History". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "An outline of Turkish History until 1923". byegm.gov.tr. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. "Xiongnu 匈奴 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". www.chinaknowledge.de. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ G. Pulleyblank, "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese: Part II", Asia Major n.s. 9 (1963) 206–65

- ^ Kessler, P L. "The Origins of the Huns". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Carter V. Findley, The Turks in World History (Oxford University Press, October 2004) ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- ^ Jackson, P. (2002). "Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens". Journal of Islamic Studies. 13 (1). Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies: 75–76. doi:10.1093/jis/13.1.75.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 574.

- ^ "The Seljuks of Rum". davidmus. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Inalcık, Halil (1978). The Ottoman Empire: conquest, organization and economy. Variorum ReprintsPress. ISBN 978-0-86078-032-8.

- ^ a b Jay Shaw, Stanford; Kural Shaw, Ezel (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7.

- ^ İsmail Hakkı Göksoy, "Ottoman-Aceh relations as documented in Turkish sources" in Michael R. Feener, Patrick Daly, and Anthony Reid, Mapping the Acehnese Past (Leiden: KITLV, 2011),65-95.

- ^ Robert Bideleux, Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe, 1998, p. 86.

- ^ a b Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. pp. 167, 185, 193, 211–12, 248, 363. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- ^ Bjørnlund, Matthias (2008). "The 1914 cleansing of Aegean Greeks as a case of violent Turkification". Journal of Genocide Research. 10 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1080/14623520701850286.

- ^ Kaligian, Dikran (2017). "Convulsions at the End of Empire: Thrace, Asia Minor, and the Aegean". Genocide in the Ottoman Empire: Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks, 1913–1923. Berghahn Books. pp. 82–104. ISBN 978-1-78533-433-7.

- ^ Schaller, Dominik J; Zimmerer, Jürgen (2008). "Late Ottoman genocides: the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and Young Turkish population and extermination policies – introduction". Journal of Genocide Research 10 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1080/14623520801950820

- ^ Üngör, Uğur Ümit (2012). "The Armenian Genocide, 1915" (PDF). Holocaust and Other Genocides (PDF). NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies / Amsterdam University Press. pp. 45–72. ISBN 978-90-4851-528-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015). "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press. pp. 374–375. ISBN 978-1-4008-6558-1.

- ^ Roderic H. Davison; Review "From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920" by Paul C. Helmreich in Slavic Review, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Mar. 1975), pp. 186–187

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas, p. 237. ISBN 0-226-33228-4

- ^ Psomiades, Harry J. (2000). The Eastern Question, the Last Phase: a study in Greek-Turkish diplomacy. Pella. pp. 27–38. ISBN 0-918618-79-7.

- ^ Macfie, A. L. (1979). "The Chanak affair (September–October 1922)". Balkan Studies. 20 (2): 309–41.

- ^ Heper, Metin; Criss, Nur Bilge (2009). Historical Dictionary of Turkey. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6281-4. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Darwin, J. G. (February 1980). "The Chanak Crisis and the British Cabinet". History. 65 (213): 32–48. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1980.tb02082.x.

- ^ Dawson, Robert MacGregor (1958). William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Political Biography, 1874-1923. University of Toronto Press. pp. 401–416.

- ^ "The Treaty of Sèvres, 1920". Harold B. Library, Brigham Young University. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ a b Mango, Andrew (2000). Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. Overlook. p. lxxviii. ISBN 978-1-58567-011-6.

- ^ Axiarlis, Evangelia (2014). Political Islam and the Secular State in Turkey: Democracy, Reform and the Justice and Development Party. I.B. Tauris. p. 11.

- ^ Clogg, Richard (2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Gerhard Bowering; Patricia Crone; Wadad Kadi; Devin J. Stewart; Muhammad Qasim Zaman; Mahan Mirza (2012). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4008-3855-4. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

Following the revolution, Mustafa Kemal became an important figure in the military ranks of the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) as a protégé ... Although the sultanate had already been abolished in November 1922, the republic was founded in October 1923. ... ambitious reform programme aimed at the creation of a modern, secular state and the construction of a new identity for its citizens.

- ^ Kinross, John (2001). Atatürk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey. Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1842125991.

- ^ "TURKISH BAN ON FREEMASONS. All Lodges To Be Abolished". Malaya Tribune, 14 October 1935, p. 5. The Government has decided to abolish all Masonic lodges in Turkey on the ground that Masonic principles are incompatible with nationalistic policy.

- ^ "Tageseinträge für 14. Oktober 1935". chroniknet. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Atatürk Döneminde Masonluk ve Masonlarla İlişkilere Dair Bazı Arşiv Belgeleri by Kemal Özcan

- ^ Hassan, Mona (10 January 2017). Longing for the Lost Caliphate: A Transregional History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8371-4. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Soner Çağaptay (2002). "Reconfiguring the Turkish nation in the 1930s". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 8 (2). Yale University: 67–82. doi:10.1080/13537110208428662. S2CID 143855822.

- ^ Erik J. Zurcher, Turkey: A Modern History (3rd ed. 2004) pp 203-5

- ^ A. C. Edwards, "The Impact of the War on Turkey," International Affairs (1946) 22#3 pp. 389-400 in JSTOR Archived 2016-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huston, James A. (1988). Outposts and Allies: U.S. Army Logistics in the Cold War, 1945–1953. Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 978-0-941664-84-4. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Timeline: Cyprus". British Broadcasting Corporation. 12 December 2006. Archived from the original on 16 December 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Hale, William Mathew (1994). Turkish Politics and the Military. Routledge, UK. ISBN 978-0-415-02455-6.

- ^ "Turkey's PKK peace plan delayed". BBC. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ Nas, Tevfik F. (1992). Economics and Politics of Turkish Liberalization. Lehigh University Press. ISBN 978-0-934223-19-5.

- ^ "25th Anniversary of Gazi Massacre Marked". bianet.org.

- ^ "Recep Tayyip Erdogan wins Turkish presidential election". BBC News. 10 August 2014. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Turkey's coup attempt: What you need to know". BBC News. 16 July 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Who was the Ankara assassin?". ABC News. 20 December 2016. Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ "Erdoğan clinches victory in Turkish constitutional referendum". the Guardian. 16 April 2017. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Turkey election: Erdogan wins re-election as president". BBC News. 24 June 2018. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "MBS approved operation to capture or kill Khashoggi: US report". Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Turkey is now Türkiye: What other countries have changed their name?". euronews. 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Wilks, Andrew. "Turkey's Erdogan celebrates presidential election run-off win". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Uncertain Futures: Ukrainian Refugees in Turkey, One Year On". pulitzercenter.org. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ Airport, Turkish Airlines planes are parked at the new Istanbul (24 July 2023). "Russian migration to Turkey spikes by 218% in aftermath of Ukraine war - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com.

- ^ "Number of Syrians in Turkey July 2023 – Refugees Association". multeciler.org.tr.

- ^ Sharp, Alexandra (11 April 2024). "Turkey's Opposition Wins 'Historic Victory' in Local Elections". Foreign Policy.

Sources

- Ahmad, Feroz. The Making of Modern Turkey (Routledge, 1993),

- Barkey, Karen. Empire of Difference: The Ottomans in Comparative Perspective. (2008) 357pp excerpt and text search

- Bellwood, Peter (2022). The Five-Million-Year Odyssey. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9780691236339. ISBN 978-0-691-19757-9.

- Eissenstat, Howard. "Children of Özal: The New Face of Turkish Studies" Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 1#1 (2014), pp. 23–35 DOI: 10.2979/jottturstuass.1.1-2.23 online

- Findley, Carter V. The Turks in World History (2004) ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- Findley, Carter V. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History (2011)

- Finkel, Caroline. Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire (2006), standard scholarly survey excerpt and text search

- Freeman, Charles (1999). Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198721943.

- Goffman, Daniel. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe (2002) online edition Archived 23 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Goodwin, Jason. Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire (2003) excerpt and text search

- Hale, William. Turkish Foreign Policy, 1774–2000. (2000). 375 pp.

- Hornblower, Simon; Antony Spawforth (1996). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Howard, Douglas A. (2016). The History of Turkey (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-4408-3466-0.

- Inalcik, Halil and Quataert, Donald, ed. An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914. 1995. 1026 pp.

- Kedourie, Sylvia, ed. Seventy-Five Years of the Turkish Republic (1999). 237 pp.

- Kedourie, Sylvia. Turkey Before and After Ataturk: Internal and External Affairs (1989) 282pp

- E. Khusnutdinova, et al. Mitochondrial DNA variety in Turkic and Uralic-speaking people. POSTER NO: 548, Human Genome Organisation 2002

- Kinross, Patrick. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire (1977) ISBN 0-688-03093-9.

- Kosebalaban, Hasan. Turkish Foreign Policy: Islam, Nationalism, and Globalization (Palgrave Macmillan; 2011) 240 pages; examines tensions among secularist nationalism, Islamic nationalism, secular liberalism, and Islamic liberalism in shaping foreign policy since the 1920s; concentrates on era since 2003

- Kunt, Metin and Woodhead, Christine, ed. Süleyman the Magnificent and His Age: The Ottoman Empire in the Early Modern World. 1995. 218 pp.

- Lloyd, Seton. Turkey: A Traveller’s History of Anatolia (1989) covers the ancient period.

- Mango, Andrew. Ataturk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey (2000) ISBN 1-58567-011-1

- Mango, Cyril. The Oxford History of Byzantium (2002). ISBN 0-19-814098-3

- Marek, Christian (2010), Geschichte Kleinasiens in der Antike C. H. Beck, Munich, ISBN 9783406598531 (review: M. Weiskopf, Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2010.08.13).

- McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon, eds. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

- McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (2012a). "Introduction: The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 3–12. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0001

- McMahon, Gregory. "The Land and Peoples of Anatolia through Ancient Eyes". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 15–33. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0002

- Matthews, Roger. "A History of the Preclassical Archaeology of Anatolia". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 34–55. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0003

- Steadman, Sharon. "The Early Bronze Age on the Plateau". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 229–259. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0010

- Michel, Cécile. "The Kārum Period on the Plateau". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 313–336. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0013

- Khatchadourian, Lori. "The Iron Age in Eastern Anatolia". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 464–499. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0020

- Greaves, Alan M. "The Greeks in Western Anatolia". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 500–514. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0021

- Beckman, Gary. "The Hittite Language: Recovery and Grammatical Sketch". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 517–533. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0022

- Yakubovich, Ilya. "Luwian and the Luwians". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 534–547. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0023

- Zimansky, Paul. "Urartian and the Urartians". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 548–559. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0024

- Sams, G. Kenneth. "Anatolia: The First Millennium B.C.E. in Historical Context". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 604–622. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0027

- Melchert, H. Craig. "Indo-Europeans". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 704–716. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0031

- Jablonka, Peter. "Troy in Regional and International Context". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 717–733. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0032

- Radner, Karen. "Assyrians and Urartians". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 734–751. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0033

- Harl, Kenneth W. "The Greeks in Anatolia: From the Migrations to Alexander the Great". In McMahon & Steadman (2012), pp. 752–774. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0034

- Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State (1969). excerpt and text search

- Quataert, Donald. The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 (2005), standard scholarly survey excerpt and text search

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808–1975. (1977). excerpt and text search ISBN 0-521-29163-1

- Thackeray, Frank W., John E. Findling, Douglas A. Howard. The History of Turkey (2001) 267 pages online Archived 29 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Vryonis Jr., Speros. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century (1971).

- Zurcher, Erik J. Turkey: A Modern History (3rd ed. 2004) excerpt and text search